“If anyone comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters—yes, even their own life—such a person cannot be my disciple.” (Luke 14:26)

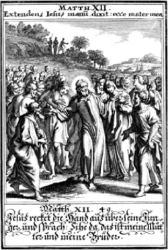

Apparently Jesus himself is one of his best disciples, as we read in Matthew 12:46-50: “While Jesus was still talking to the crowd, his mother and brothers stood outside, wanting to speak to him. Someone told him, “Your mother and brothers are standing outside, wanting to speak to you.” He replied to him, “Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” Pointing to his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers. For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.”

How is it possible that a religion built on the idea of Love embraces hatred, hatred even with regard to the ones we naturally love the most: father, mother, brothers, sisters – ‘elementary kinship’, Lévi-Strauss would say?

Yet, this is not without a logic behind it. For Love, as the central paradigm in Christianity, is primordially not a family affair, but a social, political, and even cosmic matter. It is the alternative to the Law, paradigm of the Old Covenant, where it was the Chosen People’s instrument to restore its broken relation with God. That people failed in fulfilling the Law, which is why God intervened and sent his own Son in order to take upon him the debt caused by that failure. Which is what happened, and he saved not only that particular people, but the whole of mankind, the entire universe. That act of Love, done by the Father’s sacrifice of his Son, delivered the world from sin and death, and turned it into a New Creation. Living in the realm of that deliverance, breathing the freedom beyond the Law: this is what Christian Love is about.

So, beyond the love attachment of family and friends, there is a divine Love that unites the loving person to all humans and even to the entire universe. Hence, not totally illogical, the commandment to hate the particular and the intimate: sisters, brothers, mother and (even) father, for there is only one Father, who is in heaven. In this, Christian Love is thoroughly monotheist: it concerns the truth, which is universal and, consequently, excludes the singular. A singular god is a false one, for there is only one God who for that very reason is the God of everyone. This is why a logic of exclusion is inherent to monotheism: to love God is to hate idols.

To love God is to hate what he hates.

This is why hate can even enter Christianity’s mystic love tradition. Take, for instance, Hadewijch of Brabant (13th century) who in her Fifth Vision writes (v. 18-20):

Manuscript of Hadewijch's Frist Poem, Ghent, UB, 941, f. 49r.

Ic hebbe minen ghehelen wille noch met u, ende minne ende hate met u als ghi.

(I have attuned my entire will to you, I love and hate the way you love and hate.)

Or, a few lines further in the same Vision (v.52-56):

Doe ghi mi selve in u selven naemt, ende daed mi weten hoeghedaen ghi sijt, ende haet ende mine in enen wesene, doe bleef mi bekent hoe ic al met u soude haten ende minnen ende in allen wesene sijn.

(When you took me in you and let me know how you hate and love in one essence, then, I learned to hate and love entirely with you and to be similar to you in all what is.)

Here, Hadewijch’s mystical desire zooms in on the judging God, on God separating right from wrong, true from false, good from bad. The mystical union she longs for is a unification with the separating power of divine truth. But precisely the splitting character of that power keeps Hadewijch from being united with God. It is, so to say, a split in God that keeps her desire ongoing.

Loving the divine hatred, she keeps on loving/desiring thanks to that hatred.

*