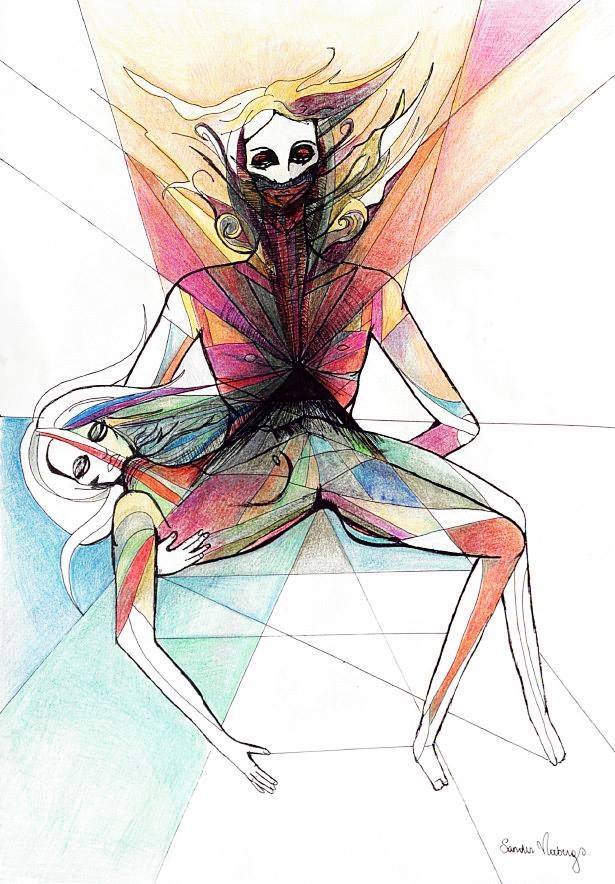

By Sander Vloebergs

This blog is a theological-artistic exploration of Laudato si based on the themes of gender and pain. For his drawing, Sander Vloebergs was inspired by the classical pieta composition and the pain that runs through it.

Mary, the Mother who cared for Jesus, now cares with maternal affection and pain for this wounded world. Just as her pierced heart mourned the death of Jesus, so now she grieves for the sufferings of the crucified poor and for the creatures of this world laid waste by human power (Laudato si 241).

The world is in pain, Mary is grieving and the Crucified mourns for the injustice that befell the Creation of the Father. In this contemporary story about the de-creation of the world, everyone seems to weep. The excruciating pain of the dismembering of the Earth blurs the lines between the protagonists of salvation history. In this blog I want to explore the divisions between the bodies in pain. Does suffering bring the Mother, the Father and the Son closer together? Can the Father weep like a Mother?

Laudato si and Gender

Critics like Emily Reimer-Barry recently explored the papal document Laudato si and highlighted the gender roles that are used to name God and the earth. It seems that this document balances between a stereotypical gender division on the one hand and the new emphasis on gender diversity – encouraged by the feminist movement – on the other. Reimer-Barry detects an ambivalence. On the one hand, the pope explores new ways to encourage a loving relation with God and the Earth that challenges traditional oppressing relations. On the other hand the pope seems to sometimes reduce paradoxes – who are characteristics of a dynamic spirituality – to dualities that are mutually exclusive. The dynamic interplay between powerful and vulnerable, earth and heaven, man and woman seems to come to a halt occasionally. This creates an unhealthy constellation that supports oppression and power structures. The Father-image is a good example of this ambiguity.

The pope uses the name Father to stress the mutual relationship between Creator and creation. He explains his choice in Laudato si 75: “The best way to restore men and women to their rightful place, putting an end to their claim to absolute dominion over the earth, is to speak once more of the figure of a Father who creates and who alone owns the world. Otherwise, human beings will always try to impose their own laws and interests on reality.” The Father-metaphor reminds us indeed of our spiritual and material dependence on the Creator. Nevertheless, Reimer-Barry points to the dangers of narrowing down the richness of the Father-metaphor. She writes: “This image [of the Father], drawn from human experiences of power and property ownership, is more akin to a patriarch who rules over his household than a loving companion who nurtures new life and cares for the vulnerable”. The wrong use of the image of Father could indeed make God a patriarch. The Father then becomes a ruler and is no longer a parent, He is no longer vulnerable. Vulnerability is traditionally described as a ‘feminine’ characteristic. Nevertheless we need the transgression of the classical gender divisions to come to an accurate perspective on the richness of the Father-metaphor. How can we enrich our metaphor of ‘Father’? What does it mean to be a father in the first place? (see Yves De Maeseneer's blog Child calls father to fatherhood). These reflections are not alien to the pope’s thinking.

Feminist theology encourages people to call God Father and Mother. This idea challenges the western dualistic way of thinking. God is both man and woman, He/She has female and male characteristics. Reimer-Barry regrets that the pope sometimes follows the dualistic divisions. She says: “By adopting masculine language for God and feminine language for Nature, Pope Francis carries forward a long-standing cultural metaphor that has been dangerous for women, given that it fails to recognize the equal dignity of women in shaping culture”. She continues: “In this worldview, to be masculine is to be strong, rational, active; to be feminine is to be weak, emotional, passive”. Nevertheless, the pope doesn’t make these divisions all the time. By emphasizing the vulnerable caring characteristics of the Father, the pope transgresses the gender roles. The Pope’s Father-image is grounded in a rich spirituality that recognizes vulnerability as a strength. The Father “also shows great tenderness, which is not a mark of the weak but of those who are genuinely strong, fully aware of reality and ready to love and serve in humility” (LS 242). He is not an oppressing patriarch but a caring parent. The Father is not a distant spectator of creation’s painful history. He chose to become vulnerable, to share blood and tears, to exchange Love and pain with his Mother Nature (the creation).

An Artistic-Theological Reflection

The Pieta – my drawing – spins around the point of vulnerability and compassion and creates an artistic Utopia where the Father can be the Mother and where the Creator can touch his creation. On this blank page Mary is allowed to be Jesus, crucified created matter that bleeds because of the sins of the world. Her openness for groundless divine Love brought her to the cross. Her lamentations finally died in a lifeless silence as her bones lay still in the hands of her Mother-Creator, wearing the face of the Son. In this Pieta, Jesus becomes the suffering Mother. Through the eyes of the Son, the Father weeps about the faith of his creation. He is powerless and vulnerable. In this last act of kenosis his tears mingle with the blood of the earth. When He sees the lifeless body of his creation He dies with Her and becomes nothing, an endless abyss of Love. This wounding/wounded Love moves beyond identity in the nameless ineffability where the protagonists of the passion story are transfigured into their essences: the lovers game between lover and beloved, Creator and Creation. Vulnerability allows humans to be humans, God to be God and both to be lovers. The vulnerable compassionate Father grieves for the sufferings of the crucified poor with the heart of the Mother and the eyes of the Son.