Ruminations from the trenches of a seminar on Job while at work in pastoral care, by Lieve Orye

“I had my mangomoment a long, long time ago. For Him it was a small gesture, for me it made all the difference. Totally unexpected, He simply showed himself in a whirlwind and reminded me of who He was and who I was. That He had been there, had cared for me since before the day I was born. Even more, He said I had spoken well, while my friends who ended up denying my innocence were told to have spoken badly. Since then things have changed dramatically, I sat up out of the dirt and ashes, found life again, life abundantly.”

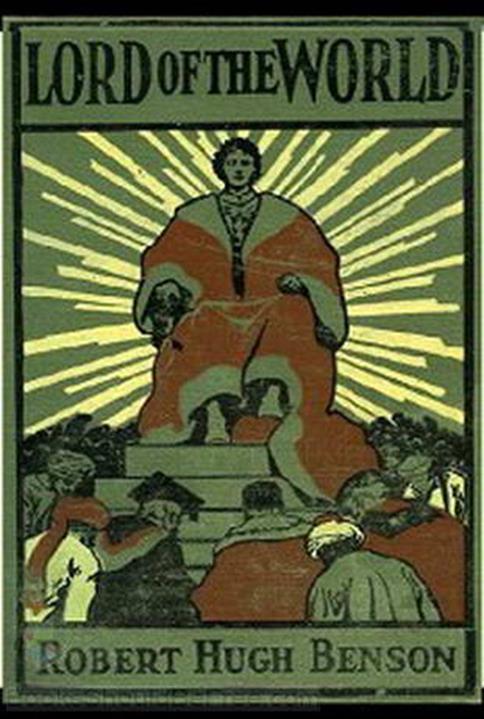

William Blake - The Lord Answering Job out of the Whirlwind'

Job’s friends: from presence to adding insult to injury

These days Job would not end up on a heap of dirt. These days he would end up at the doctor’s. Clearly Job’s friends did not medicalize Job’s suffering. At first, they sat with him, seven days, silently, because they saw that his suffering was very great. As Stanley Hauerwas sees it,

“that they did so is truly an act of magnanimity, for most of us are willing to be with sufferers, especially those in such pain that we can hardly recognize them, only if we can “do something” to relieve their suffering or at least distract their attention. Not so with Job’s comforters. They sat on the ground with Job doing nothing more than being willing to be present in the face of his suffering” (Hauerwas 1988: 78).

William Blake - Job rebuked by his friends

But then, Job cries out his misery. As Bruno Latour points out, in his discussion of the deep cry of the earth in Laudato Si, a cry “is not a message, a doctrine, a slogan, a piece of advice or a fact but rather something like a signal, a rumor, a stirring or an alarm. Something that makes you sit up, turn your head and listen.”[1] His friends, however, don’t hear the cry in his cry. His cry is heard as a question mark to an understanding of the world they hold dear and their response is to apply a causal moral model to his misfortune. Their theory of retribution results in pointing fingers, blaming Job for his own suffering, adding insult to injury. They offer Job a logical God, one who takes an account book approach to sin and suffering. But Job’s experience is dramatically at odds with the dogma his friends urge on him and whereas they were present to him in their shared silence, willing to be with him, they now stand over against him in their speaking, unable to see how Job’s unwillingness to see things their way is not a matter of logic but of hurt.

From technical medicine to ‘mangomoments’

Causal moral explanations for suffering have now mostly made way for technical explanations. As Job’s friends we now might be more keen to medicalize his suffering. Uncomfortable with remaining present without doing something, Job would be taken to the emergency room to get his skin condition treated and further to the psychiatric ward for treatment of his depression, where he might be commended for not blaming himself for his situation. And if his friends would not take him, he might find his own way to the E.R. and the psychiatric ward.

“Patients and caregivers alike have increasingly medicalized suffering— understood it, that is, as a problem that medicine can successfully treat. Many view suffering as one more technical problem that medicine can solve.”(Fleischer 1999: 487)

When we suffer, or when we see others suffering, our first reponse is not to sit down and share the suffering in silence. We want things to be done. We want the doctor to apply a causal biological model that figures out what went wrong and how to put things right again so that we can be back on our way and the suffering becomes only the memory of a small detour on our journey of leading a happy life. We prefer suffering that takes the shape of a broken leg. Causes are clear, the solution is straight forward. But not all suffering – not even every broken leg - can be boxed into this square. And sufferers have indicated again and again that the cry in their cry isn’t heard. What they say is sifted through for information to be fed to the technical solution machine. And whereas those whose suffering gets alleviated, take the insult as a price to pay for their ticket out, those for whom a technical solution isn’t forthcoming experience the insult, the deafness to their cry, so much more.

Nevertheless, there are signs of a counter movement. ‘Patient centredness’ has become a key concept in health care. At a meeting of the Professional Association for Catholic Pastors in Belgium I heard Kris Vanhaecht tell the story of how a movement, called Mangomoment, was launched inspired by a striking television fragment.

Two months after waking up from coma in intensive care, Viviane described how hard it was lying in bed all the time, what the sound of the bedside alarms did to her, what the gray ceiling looked like, how she heard the voices of deceased family members and saw them standing next to her bed, and why she thought about euthanasia,… Her reflections were captured on a documentary by a journalist, Annemie Struyf, who stayed for two weeks as an observer at an intensive care unit, and who was clearly emotional as she was touched by Viviane’s story. Following a tense silence, the journalist asked: “Is there something I can do now for you, that would make you happy?”. Viviane’s answer was surprising … “a mango, I would really like to taste a mango again, that is what I really like”. At the last day of her observation, the journalist brought Viviane a mango. Viviane was touched and became emotional, expressing that she “will never ever forget this moment”.

This story encouraged Vanhaecht to study ‘mangomoments’ in search of care that ‘is just that little something more’. As someone researching and teaching quality of care and patient safety at the KU Leuven and as someone recognizing the importance of person centred care that sees the patient as ‘a human being with a history, with desires and fears,’ he coined this new term.

“A caregiver who, with a little gesture or an unexpected act of attentiveness, creates a moment of great value for a patient… that is a Mangomoment”[2]

Three minutes, seven days and a life-time

Mangomoments consist of those little things we do for a patient that make a memorable difference crucially because he or she feels strongly recognized as the person he or she is beyond the illness or the misery they are dealing with. Allowing someone to wear her glasses into the operation theater even though regulations are to take it off before, organising a visit of grandchildren or creating an experience of watching a movie together with a loved one, coke and popcorn included, for someone in an isolation room. These moments don’t seem to take the time Job’s friends took, sitting with him in silence for seven days. Rather these ‘mangomoments’ seem to be these unique moments in which something is done just at the right time, just in the right timbre, just right. Like an artist making one movement leaving a trace that changes the whole atmosphere of the painting.

Are these ‘mangomoment doings’ technical doings? I would think not. Though taking only a moment, I would answer the question of how long a mangomoment takes, in the same way a local artist answered the question how long it took to make a drawing of a life model.[3] “Seven minutes and fifty years,” she answered. The movements that made the drawing took seven minutes but her movements, their accurateness - just right - and their richness and subtlety, were the culmination of fifty years of attentive practice, allowing her to capture and express the soul of beings, happenings and places. A mangomoment, I would say, needs three specifications: it might for instance take three minutes, seven days and twenty five years. The little things done might only take three minutes, but the subtlety, the just-right-ness of what is done might be the culmination of both some days or weeks of attentive tending to this particular person and of years of attentive practice in care.

Life illustration by Irmine Remue of chamber orchestra Casco Phil, playing Schubert’s ‘Die Unvollednete”

God, as well, would answer the question of how long his mangomoment with Job took in three specifications. The whirlwind only took a few minutes, but He had been there, had cared for Job since before the day he was born and has been practicing attention from before the beginning of time. And it is from within this attunement to the world and to Job in his suffering that He reproaches the friends ‘to darken counsel by words without knowledge’ (William Blake). Maybe, paying attention to ‘mangomoments’ in a healthcare dominated by technical thinking and streamlining to get technical doings to perfection, is getting these streams of attentiveness ‘on the floor’ back to the surface of our critically and caringly thinking through health care. It might allow us to get the soul back into it. It might even allow us to recognize again that sitting with someone in the midst of misery even when nothing can be done and mangomoments no longer seem to materialize, can still be a work of hope, shaped by minutes and days and years of attentively practicing the presence of God.

[1] Latour, B. (2016) 'The Immense Cry Channeled by Pope Francis', Environmental Humanities, 8(2), 251-255.

[2] Vanhaecht’s neologism became a movement in Flanders, involving plenty of health care and welfare organisations, research and a website where mango-moment stories can be shared . Recently a book was published using these stories to inspire and motivate people to contribute to a warmer health care, with more resilience and positivity. Previously a short article ‘In Search of Mangomoments’ was published in The Lancet. ‘Mangomoment’ has become a registered trademark of the Catholic University of Leuven, with its own fund to finance scientific research.

[3] http://www.irmineremue.be/ - Remue, Irmine (2019), Un état d'âme. Edition in-house.

Hauerwas, S. (1988), Suffering Presence: Theological Reflections on Medicine, the Mentally Handicapped and the Church. Edinburgh: Clark.

Fleischer, T. (1999), ‘Suffering Reclaimed: Medicine According to Job,’ Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 42(4), 475-488.