By Tom Uytterhoeven

Research is an intellectual adventure, or so they say. In this blog post I would like to report on a recent episode in my personal adventure, in which I lost the safety of a trusted assumption, and experienced the thrill of discovering new ideas, without yet knowing where these ideas will bring me.

One of the theological metaphors that inspired my research into the theological relevance of evolutionary studies of religion, is that of kinship. Philip Hefner uses this metaphor in his book The Human Factor (1993) to express the close relationship between humanity and the rest of the global ecological community, a relationship he believes religion could and should make us more aware of. Until recently I was convinced this metaphor remedied a problematic interpretation of another metaphor used to capture the essence of Darwinism: the Tree of Life. Now, I have my doubts.

From tree and human superiority...

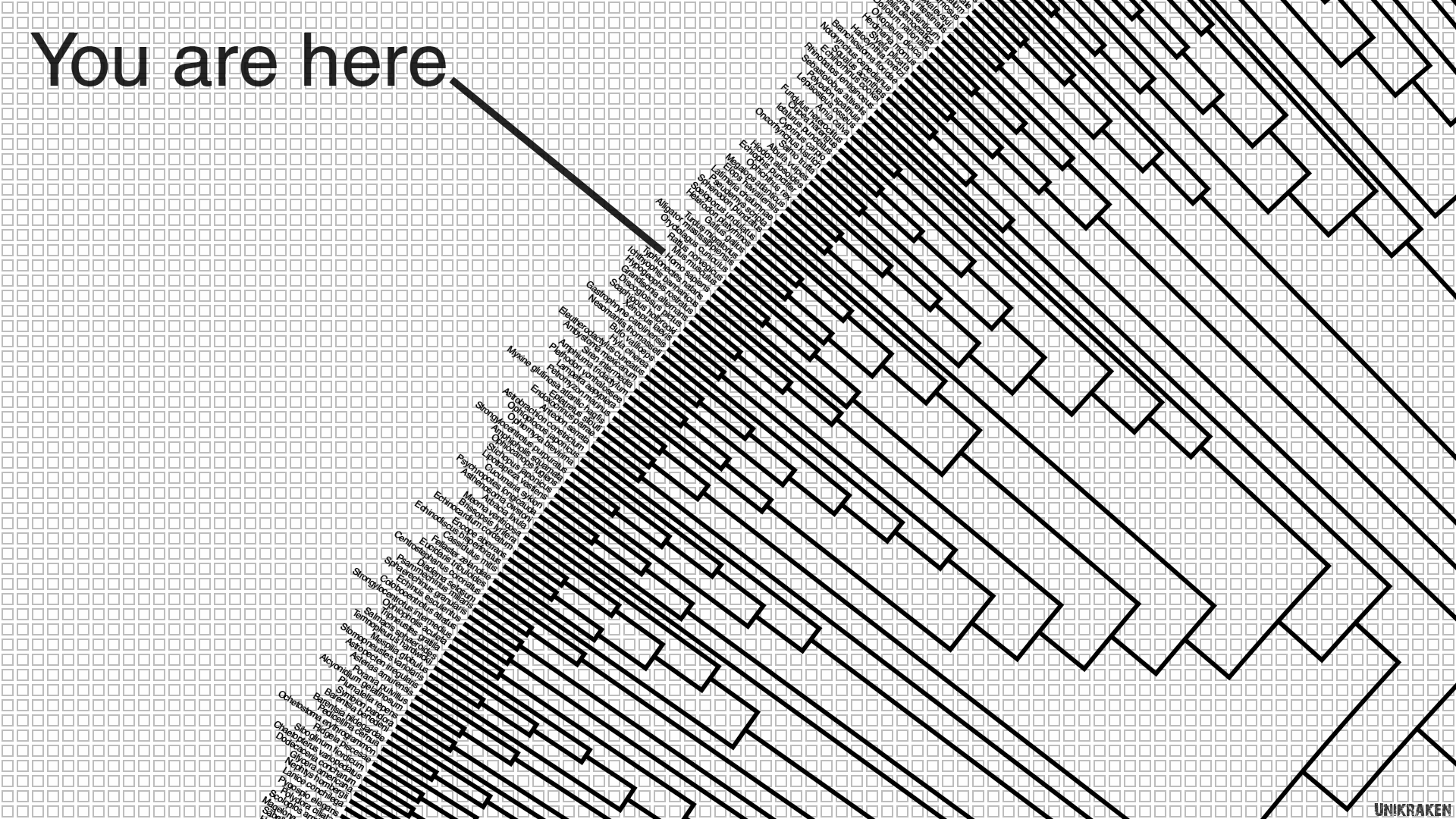

It started as a sketch in a notebook, drawn around 1837. What gave the picture of a Tree of Life, when it appeared in the first edition of the Origin of Species, an enduring appeal is that by using only a few lines, Darwin seemed to capture the essence of his ideas. Following the tree from its roots to its top, one can see the tree’s branches and twigs as species, emerging and flourishing until they faced extinction, along the way giving birth to other species. Moreover, the Tree of Life shows us that all life forms on Earth are related. Despite their apparent diversity in appearance, they all share the same roots.

Although it is interesting to see, for instance, how others before Darwin developed ‘Tree of Life’ schemata to indicate the interconnectedness of life, and how it is related to the Great Chain of Being, I want to focus here on one feature of the 'Tree of Life' metaphor which limits its metaphorical power, or, rather, which allows the metaphor to guide our thinking into an anthropocentric trap: as all trees do, a Tree of Life grows. Growth is easily associated with going upwards, in the direction of the sunlight shining down on the branches and twigs of the tree. And this, in turn, implies that the higher branches are the newest, the freshest, the greenest, in sum, the best branches of the tree. This becomes apparent in quite a few later variants on Darwin’s original sketch, in which the human species is placed on top of the tree.

Even in modern models, the human species is still often placed in a special corner. These anthropocentric depictions of Darwin’s Tree of Life are remarkable, since there is no scientific basis to give humanity an exceptional status. For as we know, there is no goal, no direction to natural selection and there is no meaning in evolution other than the survival of life, in whatever form.

... to circle and kinship?

Some current models of the Tree of Life avoid this explicit anthropocentrism by turning the phylogenetic tree into a circle. Species are placed on the circle according to their genetic relationship to each other. The closer together two species are situated in the model, the more genetic material they share. This seems to steer us away from anthropocentric interpretations of evolutionary history and to help us recognize our shared ancestry with other species. A good example of the latter is Nancy Howell’s article 'The Importance of Being Chimp'. Howell emphasizes the close genetic relationship with primates and identifies five topics which she believes theological anthropology should focus on: (1) culture-nature dualism, (2) continuity and discontinuity between humanity and other species, (3) using humanity as a measure for evaluating animal abilities, (4) the definition of personhood, and (5) morality and sin.

Far from criticizing her proposals, or similar ones, like Hefner's, that work with the same basic kinship metaphor, I nevertheless wonder whether this exchange of a tree reaching for the sky with a circle focusing on relations within allows us to take enough distance from the idea that the human species finds itself superior at the top of the tree, closest to the sun.

Destabilizing suggestions from anthropology: from lifeless to life embracing growth

For me, this question presented itself while reading Beyond Nature and Culture, a book by Philippe Descola (2013). Descola identifies four different types of perceiving the relation between humanity and nature: analogical, animistic, totemistic, and naturalistic. It would take us too far to discuss each type in depth, but it suffices here to know that they result from different combinations of perceived continuity and discontinuity between humans and nature (plants, animals, inanimate nature). What, to me at least, is both most interesting and most disturbing - in the sense of challenging my own assumptions -, is the fact that Descola refers to these types as four different ontologies, and, even more, sees naturalism - the ontology we are accustomed to - as only a recent and geographically limited one.

Reading his analysis resulted in questioning the rigid border between ‘the natural’ and ‘the cultural’, and made me aware how this boundary is easily taken to represent a qualitative leap from the former to the latter that places the human species as the species with culture again at the top. The assumption of such a border and leap is a consequence of how particular ontological axioms restrict our view rather than a consequence of taking empirical facts into account. Reading Descola, I also started wondering whether Hefner’s kinship metaphor, which in turn builds on a non-anthropocentric interpretation of the Tree of Life metaphor (see the circular model above), might be sufficient to express the close intertwinement of humanity with nature - and vice versa. Maybe we need other metaphors to express what it means to be aware of the evolutionary history of the human species, including its membership of the global ecological community.

However, reading Tim Ingold's article 'On the Distinction between Evolution and History' I came across his concept of ‘growth’ that differs radically from the rather abstract understanding that informs our usual reading of the Darwinian Tree of life and even that of the circle models of kinship. He writes:

If human beings on the one hand, and plants and animals on the other, can be regarded alternately as components of each others’ environments, then we can no longer think of the former as inhabiting a social world of their own, over and above the world of nature in which the lives of all other living things are contained. Rather, both humans and the animals and plants on which they depend for a livelihood must be regarded as fellow participants in the same world. And the forms that all these creatures take are neither given in advance nor imposed from above, but emerge within the relational contexts of this mutual involvement. In short, human beings do not, in their productive activity, transform the world; instead they play their part, alongside beings of other kinds, in the world’s transformation of itself. It is to this process of self-transformation that I refer by the concept of growth.

When reading this, it appealed to me because of its parallels with the evolutionary concept of ecological niche construction, which also stresses the multiple feedback relations between all living and non-living elements of the ecological web. What seems still missing in the latter, is this perception of life as a process of self-transformation of the world, or as the growth of the world.

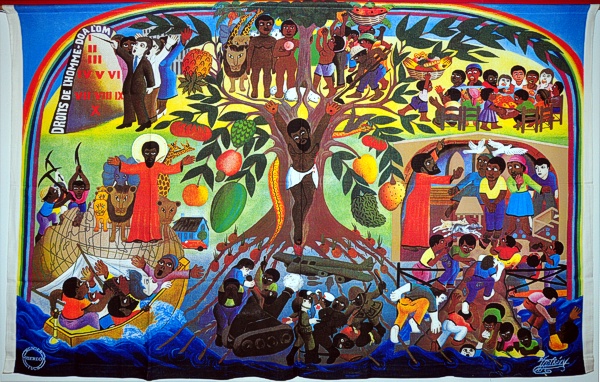

It will take more research and (self-)reflection to discover the possibilities and limits of this concept of growth for theological anthropology. But it seems to suggest that, minimally, we learn to see the Tree of Life differently. Not as lines indicating an upward movement towards a top position but through a focus on that which grows in a growing world: the tree as a whole, alive in a living reality. Perhaps the following two pictures, the first an artistic interpretation of ‘the tree of life’, the other a Christian meditation on Easter, clarify somewhat what I think this could mean.